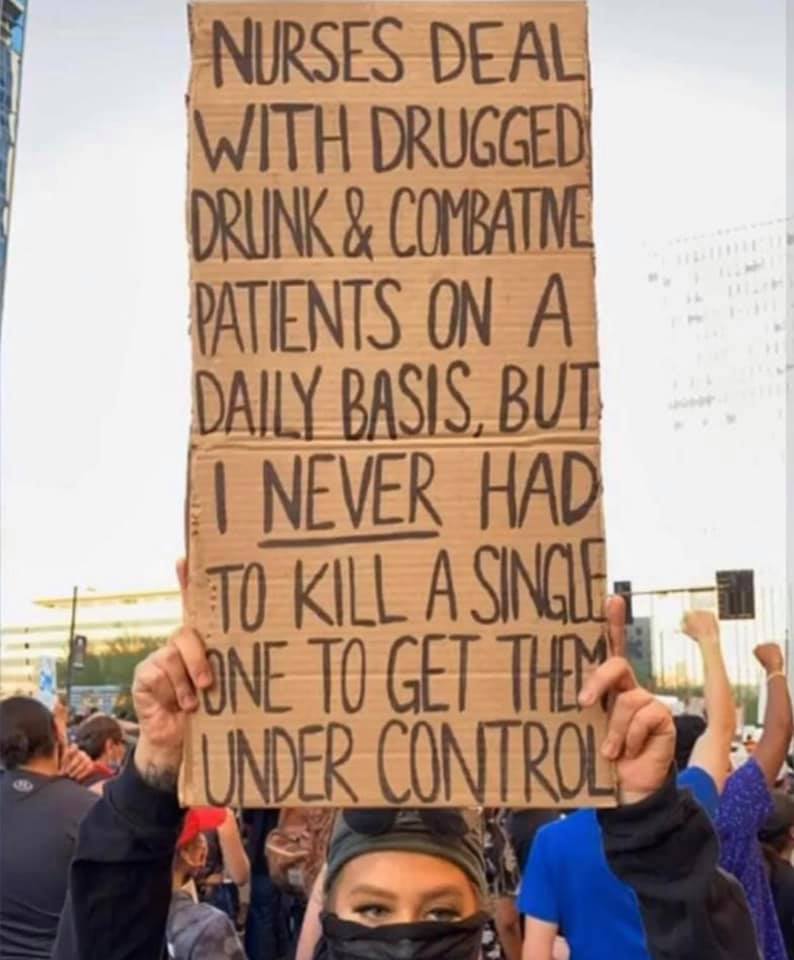

The image below is from the U.S. Democratic Socialists Facebook page.

When images like this are posted the intention is to do good. The action is intended to challenge the dominance of violence in policing. The poster wants to offer an alternative, a different narrative, one in which people who are using substances and people who are physically combative also exist and seek help and care in the hospital, in Emergency Departments etc. In these settings they are not experiencing the same level of violence by staff, nor are they dying. But is this accurate? Or are these assumptions? Do we know this data?

The nature of law enforcement and healthcare is very different. The purpose of one is to enforce the law as it is written, while the other is to treat illness, and help people and populations with health. I have worked primarily in mental health and substance use programs, inpatient, outpatient and community-based care. In my 12 year nursing career I have encountered police in the healthcare setting many times, in some programs more regularly than others. Police are in the healthcare setting. There is a problematic narrative being constructed as demonstrated in the powerful photo above, a story of an either/or of police and healthcare, of healing and harm, and it might not be well thought through.

There are many reasons why someone may be combative in the healthcare inpatient setting. Sometimes people are experiencing delirium, sometimes they have just experienced a physical or mental trauma, sometimes they have a brain injury that effects their ability to control their behaviour, sometimes it might be because they have dementia and are confused about the situation. There are many reasons why someone may be combative in a hospital setting. This is not a one size fits all, with a simple intervention. There are a variety of healthcare professionals in a hospital settings, including physicians, nurses, healthcare aids and allied health professionals. There are a variety of tools that exist within a healthcare setting that are not readily available in a community setting, nor in the general public, these tools include seclusion rooms, mechanical restraints, and medications that can be used for rapid tranquilization. The tools available in the hospital setting are different than what is available in the community.

When nurses go out in the community to assess people who are experiencing mental health crisis they can complete a comprehensive assessment. But, when we imagine the process of how these assessment can happen we have to think about the mechanism that mental health nurses and mental health clinicians who are able to complete these assessments are triaged to do this. How do they find out about the mental health crisis? Who alerts them? How do they get there? And, if someone is in imminent risk of suicide or harm towards self or others, how do they get from the community, the place they are right now, to the hospital? The current mechanism is probably calling 9-11 which goes to police, fire and ambulance. These are the groups that will first respond. When a mental health clinician goes out to assess a crisis the wellness and safety of the clinician is imperative. Unlike police, mental health clinicians do not have tools or training to handle a situation when something might go wrong in terms of violence or severe self-harm, they don’t have tools of training to handle acute violence of the person that they are assessing other than retreating and calling 9-11 for police assistance. So, there is value in having a partnership between police and mental health clinicians to respond, but also value in crisis line and 9-11 operators receiving training in how to assess the types of potential risks and who best to send out on a call.

We cannot ignore that with the structures and systems that currently exist, police are sometimes probably necessary for some parts of this process. This cannot change until we collectively take a step back and evaluate the root causes of the problems in the system, our conscious and unconscious biases, and work very swiftly and thoughtfully about how to change them, bringing together all the stakeholders, including the people who utilize these services, and people who work in community health programs who provide mental health care. Evaluation of the necessary resources, and how to best respond is necessary because most people in mental health crisis are not violent towards others. Policy makers and those with allocate funding dollars must understand that a mechanism by which people in crisis (or their families or support people) who call 9-11 for help, and are assessed to need a higher level of intervention in an acute mental health setting can safely get to the hospital. Police may not be the best group to take the lead on this, but sometimes there presence and resources are necessary, necessitating a partnership with the police, not a complete fracture.

Sometimes (often?) when people who are under the influence of substances who are in mental health crisis are brought into the Emergency Department it is by police. When people who are experiencing mental health symptoms severe enough that they require hospital intervention and do not voluntarily want to go to hospital it is via police. For example, in BC police are the group able to enforce mental health legislation to bring someone against their consent to hospital for assessment. In recent weeks and months we have heard more stories about the “wellness checks” of police that have resulted in death or violence towards people who needed mental health help. The following stories might be disturbing so caution before you click the links:

The way that some mental health legislation in Canada works right now is that people are detained under a Mental Health Act. The way this plays out sometimes is that people needing help get handcuffed an put into the back of a police vehicle to transport to hospital. This can be more of a problem if this happens in a place that isn’t a big city with hospitals equipped to do mental health assessments, with psychiatrists and nurses who can provide treatment. Containment and control also happens in the hospital setting. We have to understand that policing isn’t just done by police. Sometimes there are security and protective services staff in a hospital, with varying levels of training and understanding about mental health crisis and trauma informed practice. Sometimes harm does happen to patients. But this isn’t well studied, so to make sweeping statements about no harm or staff to patient violence happening towards patients experiencing mental health crisis in a hospital setting is problematic. We cannot assume that everything is okay simply because we haven’t collected or explored the data around it.

We need to know more. We need to know:

– what are the stats on “wellness checks”?

– who are the people who are responding?

– what are the outcomes?

– how often are people taken to hospital?

– what happens when they get to hospital?

– do we collect statistics about ethnicity, and race for people who have used these services?

Peace,

Michelle D.

Leave a comment