My head is full of cognitive roadblocks that I cannot seem to navigate around, over, or bust right through. Lately, I’ve been wrestling with a question that won’t leave me alone: How did mental health and substance use become so tightly bound together in health and health care services?

The terms now go hand in hand, so much so that they often seem interchangeable. Are these synonyms? “Mental Health and Substance Use” has become a single phrase, a unit, like salt and pepper or emo and black eye-liner. But are they synonyms? Should they be?

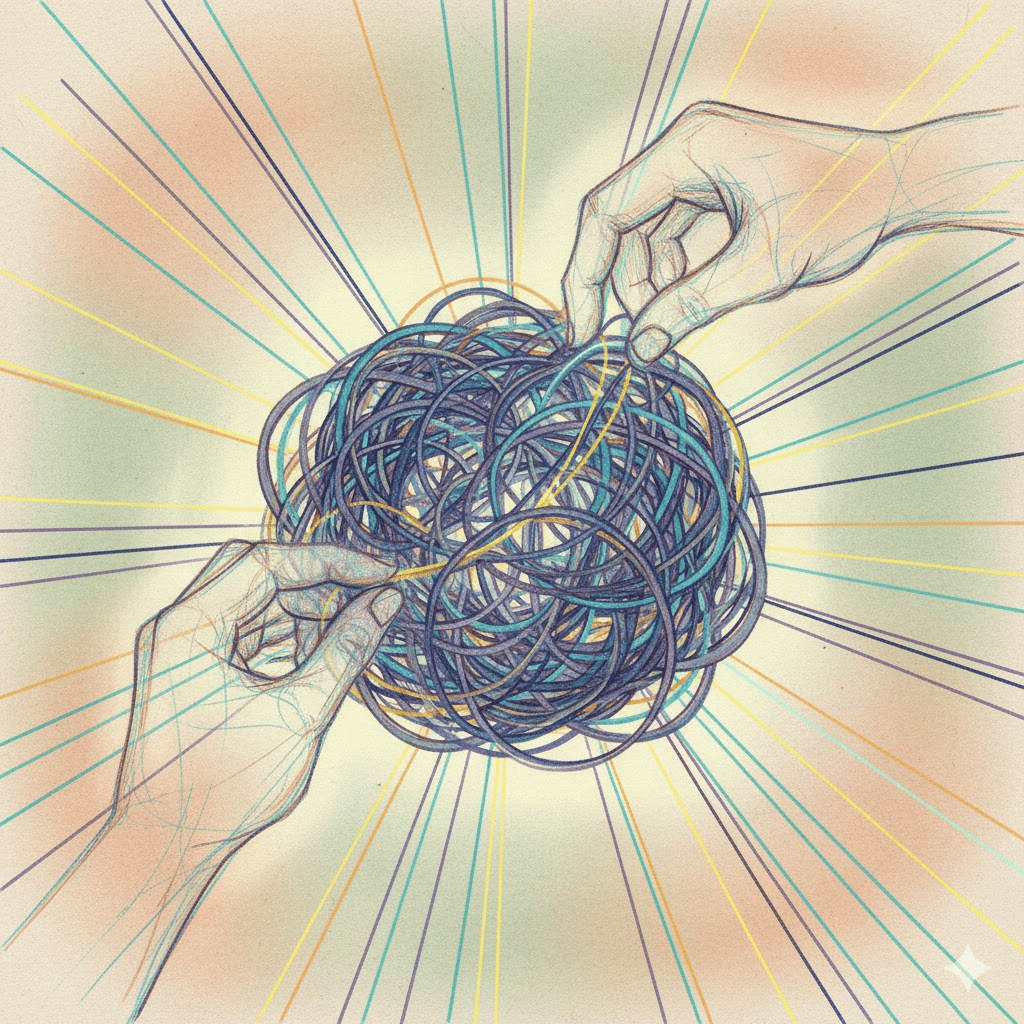

I don’t think so. And that’s why I sit here in front of my computer screen for hours, trying to untangle what I suspect is a knot of stagnation and stigma perpetuation. I’m inviting you to come with me on this journey of questioning. Be brave, take my hand and let’s do this thought experiment like you have never thought-experimented before.

The Language of Care and the Legacy of Stigma

In health services, language is never neutral. The words we use, especially the ones we combine, shape how we think, what we fund, and who we prioritize. Have I been stewing on that a while? Yes I have. The coupling of “mental health” and “substance use” is not just a convenient phrase; it represents decades of policy, clinical practice, and social narrative that have intertwined two distinct but overlapping human experiences.

Substance use as a specialty area within health care is, in many ways, a rebranding of what was once called “addictions.” The renaming was deliberate, a response to the harsh stigma that clung to addiction as a moral failing rather than a health concern. By reframing addiction as “substance use,” we hoped to reduce blame, foster empathy, and open the door to harm reduction and public health perspectives. That was a deliberate decision-making process that perhaps I might write the history of…or have I already started that journey?

To a large degree, that shift has worked. We now talk more openly about things that were once stigmatizing secrets to be shared only with those who you knew were on board with harm reduction: safe supply, overdose prevention, and trauma-informed practice. We use phrases like people who use substances instead of addicts or abusers. The shift in language has invited a shift in care.

But the shift has also blurred boundaries. It has created a conceptual space where substance use is treated as though it belongs exclusively within the realm of mental health.

Substance Use Is Not a Mental Illness

Here’s where I get this titanium cognitive block. Substance use, in and of itself, is not a mental illness. It’s a behaviour, that is it is something people do. It’s part of the human experience, sometimes joyful, sometimes social, sometimes utilitarian, sometimes devastating. For many people, it’s occasional or recreational. For others, it becomes the source of significant harm. But behaviour is not the same as pathology.

The medical model of addiction, which gained strength in the late 20th century, taught us to view substance use disorders as chronic relapsing diseases of the brain. This model had good intentions; it legitimized the suffering of people living with addiction and sought to replace punishment with treatment. Yet, it also medicalized behaviour in a way that sometimes stripped away personal and social context. There were also other questionable capitalist opportunities that emerged from this re-branding but that is an argument for another day in another blog-post.

If we define all problematic substance use as mental illness, we risk ignoring the structural and environmental factors that shape why people use. Poverty, pain, trauma, isolation, racism, lack of housing, these are not symptoms of disease; they are conditions of inequality. We cannot willfully be blind to that.

When we fold substance use entirely under mental health, we may inadvertently reinforce the idea that people who use substances are mentally ill by default. That connection is not only inaccurate but potentially harmful.

The Split Within Nursing

As a mental health nurse, I’ve been reflecting on whether our very existence as a distinct profession contributes to this ongoing division between “mind” and “body.” We know that psychiatric nursing has deep roots in the history of institutional care, born in the asylums and mental hospitals where the work of caring for those deemed “mad” was separated from general nursing practice.I did an entire PhD on this topic and continue to write about it.

Over time, psychiatric nursing developed its own philosophy, skillset, and identity. Psychiatric nursing (the distinct nursing designation) learned to see beyond symptoms, to value the therapeutic relationship, to sit with uncertainty, and to support recovery rather than cure.

Yet, as healthcare has evolved, general nursing has increasingly embraced mental health as a vital component of holistic care. Today, all nurses, whether working in emergency, community, or medical-surgical units, are expected to integrate pieces of mental health practices into their practice. It is an expectation that all nurses are competent in building therapeutic relationships and therapeutic use of self in engaging patients in their health care journey.

So I find myself asking: does the continued separation between “psychiatric nursing” and “general nursing” reflect an outdated divide between mind and body? Or does it preserve a vital area of expertise that risks being lost if we dissolve it?

There is tension here, a productive tension, perhaps, but one worth examining.

The Risks of Conceptual Clustering

When systems cluster concepts together, like mental health and substance use, it can streamline services, but it can also oversimplify complex realities. A “Mental Health and Substance Use” program might offer integrated care, which is essential for people experiencing co-occurring disorders. But that same model can struggle to meet the needs of people who use substances but do not identify with a mental illness, or those who seek harm reduction supports rather than psychiatric treatment.

In practice, it can mean someone who uses opioids and needs safer supply must first be labeled as having a mental health condition to access certain services. Or it can mean that the philosophical foundations of harm reduction (autonomy, choice, dignity) get lost within a medicalized system that still prioritizes diagnosis and compliance (don’t even get me started on that term).

The unintended consequence of integration is sometimes assimilation. Substance use care becomes a branch of mental health care rather than an equal partner beside it.

Rethinking Integration

Perhaps what we need is not separation but better differentiation. Mental health and substance use often intersect, but they are not the same. Their intersection deserves attention, but their individuality deserves respect.

Integration, when done thoughtfully, should mean partnership between disciplines, not merger into sameness. It should allow for collaboration between mental health nurses, harm reduction workers, peer supporters, social workers, and physicians, each bringing their unique lens to the work.

What if instead of trying to fold substance use under mental health, we viewed both as part of a larger ecosystem of wellness and human behaviour? What if health services were built not around disease categories but around human experiences that include things like pain, trauma, hope, connection, healing? That makes this bigger. But that makes this more holistic, and more meaningful.

The Way Forward

As nurses, we are constantly negotiating the boundaries of our work. What belongs to us? What do we share? What are we learning to let go of? Listen (or look) we as a profession and discipline evolve over time. Embrace that what we did as nurses 20 years ago is not going to be what we do today, and understand that 20 years from now nurses definitely will not be doing nursing in the exact same way they are doing it today. Hug that understanding, give it a big kiss, and put it on your cell phone contact favourites. The conversation about mental health and substance use sits at the heart of that negotiation.

To move forward, I think we must stay curious about our language and its consequences. We need to keep asking whether our structures (our departments, assessments, our clinical documentation, our job titles) reflect people’s realities or our own professional comfort zones.

And we need to remember that people who use substances are not defined by either their use or their mental health status. They are people first: people navigating a world that often misunderstands them.

Maybe the knot I’m trying to untangle is not just linguistic or conceptual. Maybe it’s ethical. Maybe it’s about how we, as healthcare professionals, define what belongs in health at all.

Closing Thoughts

I don’t have all the answers. In fact, I may have more questions now than when I started. But perhaps that’s the point. Reflection is part of practice. Reflexivity is what keeps us honest, human, and open to change.

So if you’ve read this far: good for you! I thank you for coming with me on this journey of untangling. Let’s keep asking hard questions about the systems we work in, and the language we use to describe them.

Because sometimes, naming the knot is the first step in loosening it.

Love,

Michelle D.

Leave a comment